In an innovator's school of thought, less is often more. So, simple innovations have a greater propensity to be successful. Vijay Bhaskar Reddy Dinnepu, 35, who hails from a farming family in Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh, quit his six-year stint at Cisco in August 2010 as a technical leader to do just this-use technological interventions to simplify farmers' lives.

Thanks to his brother's experience, he was familiar with the gaps in agricultural technology. Spotting scarcity of water and electricity in villages, both directly proportionate to productivity levels, he built KisanRaja-a GSM-based remote motor controller that allows farmers to control their irrigation pumps from mobile phones. Smart Home Watering System

"Agriculture has several problems and we looked at areas where technology can help," says Dinnepu, President and CEO, Vinfinet Technologies, the makers of KisanRaja.

Most villages in India receive erratic supply of electricity which farmers have to use effectively. According to Dinnepu, even progressive states like Tamil Nadu get only one to five hours at the maximum, though government books may show eight-10 hours. "Continuous power is usually available only late at night and sometimes at low voltage that's not fit to run motors," he said, adding that this is a key problem area.

As a result, farmers have to travel great distances to manually operate pumps, through difficult terrain, often encountering snakes and other hazards. "If they have more than one motor, they can't be present everywhere either," adds Dinnepu.

Motor pumps work on three-phase connectivity, the difference in voltage between each phase being 440 watts. Power from here goes to a starter that's connected to the motor which turns it on. Once the motor is on, it sucks water from the bore-well and brings it out to the fields. So KisanRaja, which weighs 1.25 kg, sits between the power phase and the starter.

"Though the functionality of a starter could be built into our device, we wanted our design to fit into their existing system so farmers don't have to change anything," explained Dinnepu. Now, KisanRaja triggers the start button on motors through a farmer's mobile phone which acts as a remote controller.

The device can be set on three modes: Manual, automatic or timer. "If power goes off during the time a motor is supposed to be on, the software's intelligence can calculate the remaining number of hours it needs to pump water once power's back," Dinnepu explained.

All commands on mobile phones are given through interactive voice response (IVR) and a farmer simply has to punch in numbers corresponding to an instruction of his choice. KisanRaja can also monitor other aspects like voltage fluctuations, wire cuts, theft or dry runs, in which case a farmer gets a call alerting him of the same. It can also be connected to submerged motors-those placed underground when water levels sink. On the security side, it doesn't accept calls from numbers that aren't configured on the device. "In such cases, it will ask for a code," pointed out Dinnepu.

KisanRaja has been sold to farmers for 6,000 each across Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka since December 2011 through dealers selling agriculture-related products. Dealers earn 15 percent from every sale.

"We realized we can't sell it ourselves. Apart from the long travel involved, you need a familiar face to sell in rural areas," Dinnepu said. KisanRaja today is a result of a nine pilots, which started in March 2011, when he tested the first prototype with farmers.

He distributed it to 60 farmers in the same two states it's sold today.

KSU Patil, who plants bananas over 2.5 acres near Mysore, has been using the device for one year and seen benefits. "I live 20 km from my farm and this has helped me manage the water distribution system better since we get power for only three hours post-midnight," he said. The company has built awareness about KisanRaja through Krishi Melas (farmer fairs) and agricultural universities. It now sells 300 pieces a month.

The earlier variant of KisanRaja weighed eight kilograms, and came with a heavy battery back-up. The new design has an in-built lithium-ion battery, similar to those found in mobile phones to decrease weight and size. "Farmers also wanted the product to be portable so they could attach it to different pumps," explained Dinnepu. Sambaiah Angirekula, Head of Soil Conservation Department, College of Agricultural Engineering evaluated the product six months ago. Based on the evaluation, Dinnepu incorporated a new battery. Nonetheless, Angirekula lauds its usefulness for the farmer community and says, "Farmers are an important national resource and we must support them. The device is technologically sound and serves both farming and farmers' needs."

Further, he had to factor in power fluctuations and so designed KisanRaja for a range of 300-500 watts. Then, the IVR language was text-bookish and incomprehensible to farmers. "It needed to be colloquial," he mentioned as a crucial change. An useful feedback incorporated was the need to keep most-used commands at the beginning. "I get alerts on my phone when the motor cannot be started. However, it doesn't mention a reason. This would be good information," said Patil in context to technological improvements.

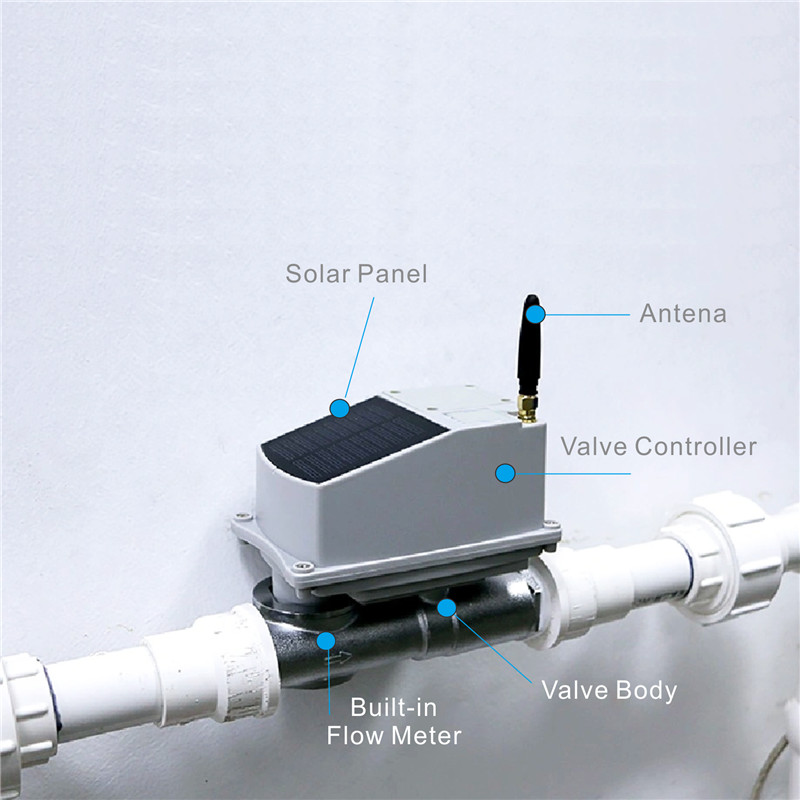

Dinnepu hasn't lost the urge to innovate. He's already working on three more variations of KisanRaja which will be ready by the time this issue of Entrepreneur is out: An ultra-light version for Rs.3,500, weighing 800 grams with minimal features; a basic version for Rs. 5,000; and one at Rs.7,500 which will be a multi-motor controller. "The product needs to be priced low to make it affordable to many farmers," he affirms. The newer versions will be water-proof and made from plastic, as opposed to the present metal exterior. Variations apart, Dinnepu is brimming with new ideas and is developing a valve controller to manage water flow.

Though KisanRaja has gained decent traction, Dinnepu is aware he will need to spend time, energy and money to create more awareness.

"We need to make the product available in the reach of 10-15 km to the farmers. This needs a huge distribution network and service centers for after-sales service," he concedes. But for now, Dinnepu's KisanRaja is bringing in a new paradigm to irrigation.

Story was first published in the Entrepreneur India

This article is supported by Spark the Rise. To know more, and to submit your ideas and projects, click here.

Join our Whatsapp channel to get the latest global news updates

It is expected that the agriculture budget for 2024-25 will follow the multi-pronged approach of supporting the sector at various levels

Ola's Bhavish Aggarwal-backed Krutrim has raised $50 million in funding, with Matrix Partners India to become India's first AI startup to get the Unicorn status. Now, the company plans to expand beyond language models, venturing into the development of data centres

The upcoming budget is not just about economic reform but about having an ecosystem where start-ups can thrive, innovate, and contribute significantly to a thriving business environment. There are several areas in which the 2024-25 budget can bring in some changes

Smart Irrigation Copyright © 2024. Firstpost - All Rights Reserved.